Working with Large & Complex Value Streams

This article outlines a practical approach to scaling Value Stream Thinking in large organizations. It begins with a strategic decision and unfolds along two coordinated paths – a global path and a local path. Each path moves through two phases: first, the identification and setup of value streams; then, the ongoing optimization and continuous improvement of the new setup.

Introduction

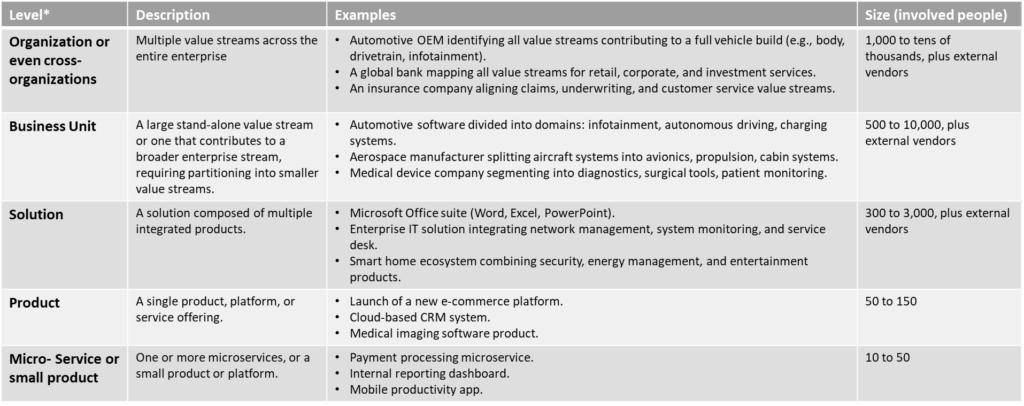

Having explored how to identify and set up small to medium-sized value streams, we now shift our focus to scaling the approach. One of the first challenges lies in understanding the true scope of the activity. The table below provides a starting point for orientation and illustration, rather than a complete or final definition.

Once the scope is understood and it becomes clear that this is a larger endeavor, a clear, structured model and approach are needed to build the value stream landscape.

Modeling Complex Value Stream Landscapes

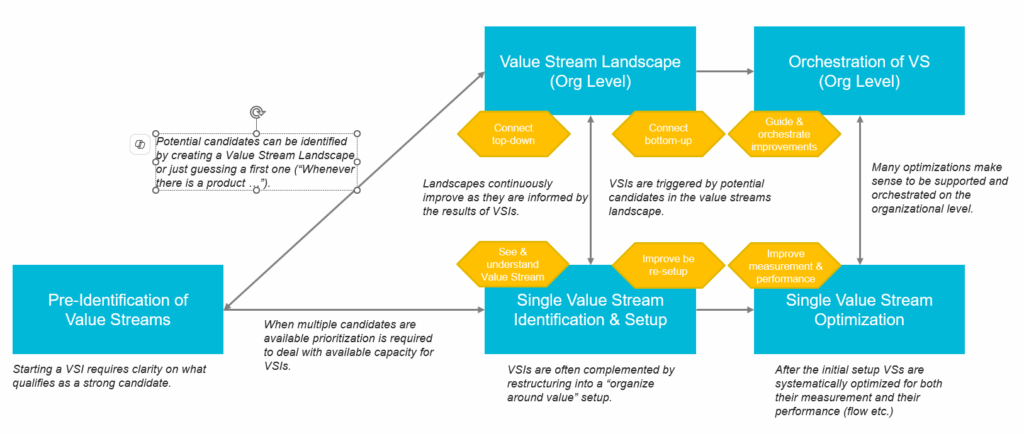

You may know the analogy of how to eat an elephant – yes, one bite at a time. Translated to Value Streams, this means that even large1 and complex development organizations must approach transformation incrementally. One effective strategy is to partition the system and tackle it from both directions: top-down by mapping a high-level Value Stream Landscape across the organization, and bottom-up by conducting focused Value Stream Identification (VSI) efforts in selected areas. These single VSIs generate actionable insight and early wins, while the top-down landscape provides strategic structure and alignment. Over time, both perspectives converge – meeting in the middle to form a more complete and evolving picture of how value truly flows. This iterative approach enables organizations to continuously refine their understanding, prioritize improvements, and scale transformation sustainably.

Managing Value Streams on the Organizational Level

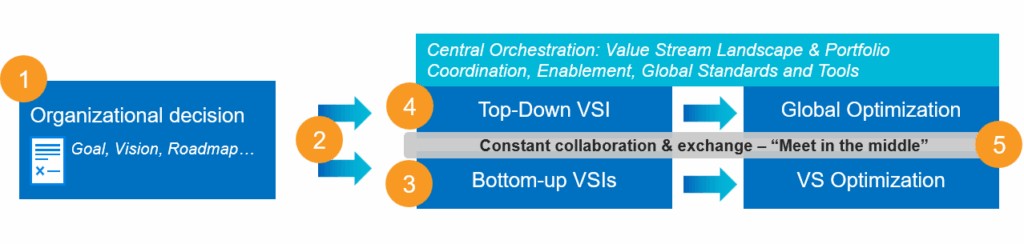

The illustration below presents a schematic approach to scaling Value Stream Thinking. It begins with the organizational decision and expands into two coordinated paths. The first phase focuses on identifying and establishing value streams, while the second emphasizes optimizing the new setup for continuous improvement.

1 – Organizational decision to Work with Value Streams

Successfully managing value streams at a global level requires organizational commitment, a shared belief in the benefits of the approach, and a clear decision to pursue it. This includes allocating the right people and capacity, as well as ensuring active support and involvement from leadership. Since these activities are not isolated efforts and rely on several supporting elements for implementation, Value Stream Thinking is typically embedded within a broader Lean-Agile transformation or a similar enterprise-wide change initiative. The goal, vision, and roadmap for creating the overall value stream landscape and organizing around value should be integral components of such an initiative.

2 – The Global and the Local Path

As mentioned, experience shows that the most effective way to establish successful value streams is through a “top-down, bottom-up, meet-in-the-middle” approach. This means working along two coordinated paths: local and global.

On the local level, teams start small with focused initiatives, conducting standard Value Stream Identifications (VSIs) in specific areas. In parallel, a central team takes a top-down view, developing a comprehensive Value Stream Landscape to guide alignment across the organization.

It’s essential that the two paths remain in close and continuous exchange. The global path learns from the experiences of local initiatives—capturing patterns, aligning the big picture with on-the-ground findings, and establishing best practices and guidelines to steer and scale the effort. Meanwhile, the local path focuses on actual execution and implementation—bringing the approach to life and providing valuable feedback on the practicality and impact of global guidance. This ongoing dialogue ensures that strategy and execution remain connected and mutually reinforcing.

We illustrate this with a SAFe-based implementation—not as the only possible model, but as one proven structure. In this setup, central orchestration occurs at the portfolio level, while local execution takes place at the ART (Agile Release Train) or Solution level.

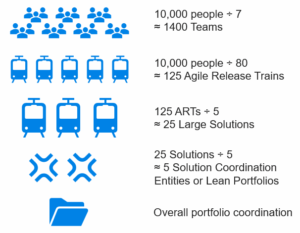

Neuroscience suggests a natural limit to effective collaboration, see Dunbar’s Number.3 We apply this principle when scaling Agile organizations. A rough calculation could look like this:

- A team consists of about 5-9 people

- An Agile Release Train (ART) typically includes 50–125 people.

- A Large Solution usually coordinates 2–6 ARTs.

- ARTs in Large Solutions should be smaller than in a single ART; ~80 people per ART is a good average

- A Lean Portfolio can govern 3–7 Solutions, depending on complexity.

These heuristics support manageable coordination and scalable structures aligned with cognitive and organizational constraints. In our example this introduces an extra level to the SAFe standard levels.

3 – The Role of the Local Path

The local path represents a bottom-up approach that begins by identifying and organizing the first value streams, selecting promising candidates, and initiating early Value Stream Identification (VSI) efforts. This selection can be guided by an existing global overview—if one exists—or emerge organically by starting where there’s a clear opportunity or strong local fit. Insights gained from these early efforts are shared with the global path to consolidate learning, refine the evolving Value Stream Landscape, and provide feedback on the VSI process itself. This includes input on needed support structures such as leadership alignment, tooling, standardization, and guidance.

4 – The Role of the Global Path

The global path is responsible for developing and maintaining an organizational overview of the Value Stream Landscape. It supports local initiatives by providing VSI experts, training, coaching, and guidance on the expected outcomes and the standardized format of work products. Equally important, it incorporates feedback from local efforts to continuously refine its enablement strategy—adapting support, tools, and guidance to better serve evolving needs.

Since the newly defined value streams must also be managed from a portfolio perspective, the global path is responsible for establishing the processes and structures that connect strategy to execution. The specific approach will vary depending on the organization’s philosophy and development methodology.

5 – Optimization

After the initial value streams are identified and set up, the organization must shift its focus toward continuous improvement. This involves two key dimensions: improving the performance of each individual value stream, and enhancing the insight and visibility into how value flows—through better telemetry, metrics, and analytics. These insights help uncover current bottlenecks, opportunities for automation, and sources of waste.

Another important focus is optimizing the interfaces and interactions between value streams. Initial VSI iterations are rarely perfect—refinements are often needed, especially around boundaries and handoffs.

While most of these improvement activities occur along the local path, they require strong support from the global path. This includes establishing shared processes, tools, and data standards to ensure a consistent, seamless experience across the value stream landscape—avoiding fragmented or incompatible tooling that can undermine collaboration and efficiency.

Conclusion

Working with large and complex value streams requires more than scaling existing practices—it demands intentional design, strategic alignment, and continuous learning. By combining top-down structure with bottom-up insight, organizations can successfully model, manage, and evolve their value stream landscape in a way that reflects how value truly flows.

Establishing a global-local collaboration model enables organizations to balance strategic direction with practical implementation. The global path provides alignment, tooling, and guidance, while the local path drives real-world execution and surfaces critical feedback. This interplay is essential for sustainable transformation—especially in enterprises with thousands of people and multiple interdependent domains.

Once the initial value streams are defined and launched, the focus should extend to continuous improvement. This includes optimizing the performance of individual value streams and improving insight and visibility through telemetry, flow metrics, and analytics to identify bottlenecks, opportunities for automation, and sources of waste. Additionally, the boundaries and interfaces between value streams often need refinement, as early VSI iterations are rarely perfect.

While most of this work happens locally, it requires consistent support from the global path—establishing shared processes, tools, and data standards to avoid fragmentation and ensure coherence across the value stream landscape.

Ultimately, large-scale value stream design is not a one-time initiative. It’s an evolving organizational capability—one that connects strategy to execution, drives operational flow, and strengthens the organization’s ability to adapt, learn, and deliver customer value at scale.

References

- A car manufacturer and its associated car development process provide a good example of a large value stream. This type of value stream is undeniably large – often involving thousands of engineers, designers, and suppliers across multiple domains. Yet despite its scale, the goal remains clear: to release a new car model.

However, the complexity doesn’t stop there. Each model is typically delivered in multiple variants to serve different markets and customer needs. These may include differences in drivetrain (e.g., front-wheel drive, rear-wheel drive, or all-wheel drivee), driver seat placement (left-hand vs. right-hand drive), body styles (such as sedan vs. wagon), or even powertrain configurations, including combustion engines, hybrid systems, or fully electric platforms. Based on real-world experience, a single model can result in thousands of possible configurations. ↩︎ - This is still a simplified view — larger organizations often include one or two additional layers between the two shown here. ↩︎

- Robin Dunbar (1992). Neocortex size as a constraint on group size in primates. Journal of Human Evolution, 22(6), 469–493. à https://doi.org/10.1016/0047-2484(92)90081-J and

Dunbar, R. (1998). The social brain hypothesis. Evolutionary Anthropology: Issues, News, and Reviews, 6(5), 178–190. à https://doi.org/10.1002/(SICI)1520-6505(1998)6:5<178::AID-EVAN5>3.0.CO;2-8 ↩︎

Author: Peter Vollmer – Last Updated on September 10, 2025 by Peter Vollmer