Defect Escape Rate

Definition and Purpose

Defect Escape Rate (DER) is a quality metric that measures the percentage of defects that are not detected at an intended stage of the value stream and instead surface later. It shows where feedback mechanisms fail to detect specific defect types early enough.

A high escape rate is a strong signal of missing, ineffective, or misaligned feedback. It indicates gaps in test strategy, automation, engineering practices, or integration discipline. As such, DER is not a local quality metric – it is a leading, system-level indicator for improving upstream quality and end-to-end flow.

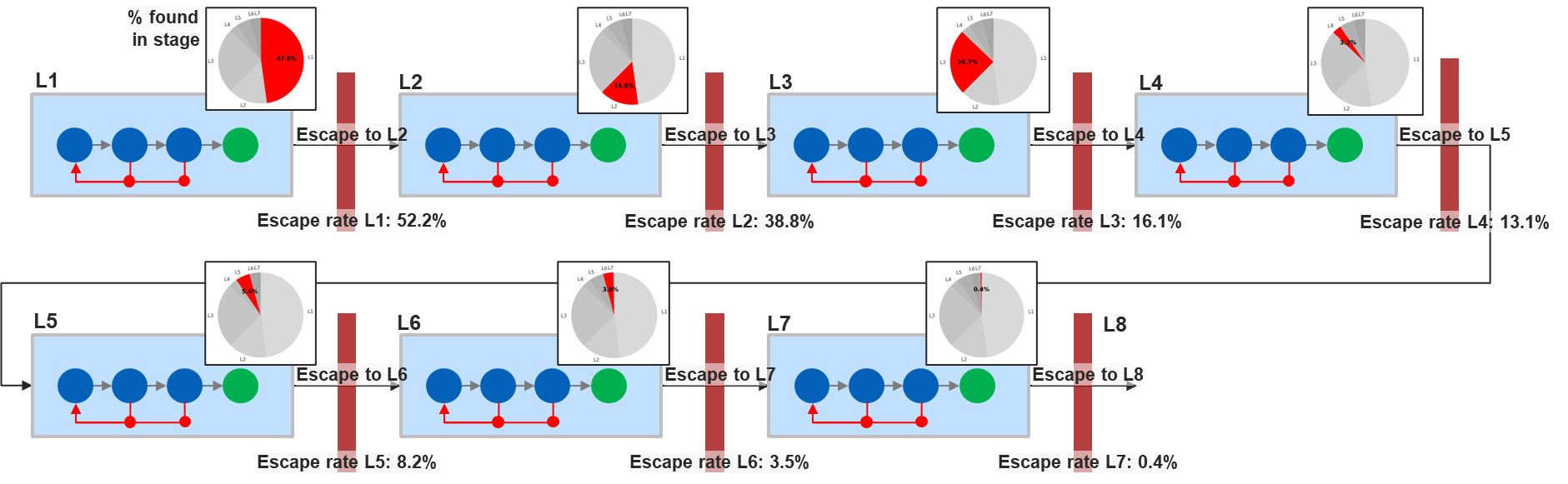

The diagram illustrates how defects flow through successive test and integration stages, where they are detected, and where they escape to later stages.

Why it matters: The Economics of Escaped Defects

Defects that escape early detection carry a non-linear cost increase as they move downstream. Later discovery typically means:

- longer feedback cycles

- loss of context and intent

- higher coordination effort across teams

- increased rework and revalidation

- and a growing blast radius of change

What appears as a single late defect often represents accumulated waste that has already propagated through the value stream. This makes DER fundamentally an economic signal: it reveals where learning happens too late and where preventable cost is being introduced into the system.

Defect Escape Rate as a Diagnostic Signal

DER does not exist to assign blame. Escaped defects are learning signals.

By analyzing where defects escape – and which defect types escape from which stages – organizations gain concrete insight into:

- which feedback mechanisms are missing or ineffective

- which assumptions are validated too late

- and where test effort is compensating for earlier gaps rather than preventing them

DER therefore shifts the conversation from “How many defects do we have?” to “Why does the system fail to learn earlier?”

Assembly Line View: Local and System-Wide Escape Rates

The Assembly Line Model provides a natural structure for observing defect escapes. At a single stage, DER answers a local question: How effective is the testing owned by this stage?

Across the entire value stream, DER reveals system behavior: Where does the system rely on downstream inspection instead of upstream prevention?

By composing multiple component-level assembly lines into a larger structure, the same logic scales from individual components to large and very large value streams. This enables consistent measurement of escape rates within sub-streams and across integration boundaries, using a shared model and language. Local improvements can then be validated against their system-wide effect, preventing sub-optimization.

The diagram shows how defects flow across sub-streams and integration stages of the end-to-end value stream.

As a result, teams can improve quality and flow within their own area of responsibility, while leadership gains transparency into system-wide behavior and bottlenecks. Local optimizations are therefore guided and validated in the context of overall value stream performance, ensuring that improvements contribute to end-to-end flow rather than sub-optimizing isolated parts of the system.

Using Defect Escapes as a Learning Instrument

Escaped defects are not failures — they are signals that the system learned too late. When analyzed systematically, they provide concrete input for improving test strategy and feedback design.

1) A useful analysis starts with a small set of disciplined questions:

- From which stage did the defect escape?

- What signal, test, or check was missing or ineffective at that stage?

- Could this defect realistically have been detected earlier?

- Do similar defects escape repeatedly in the same way?

2) Answering these questions shifts the conversation from counting defects to understanding why learning happened late.

Insights from escaped defects typically lead to targeted system improvements, such as:

- adding or refining tests at the stage where the signal is cheapest

- improving automation or coverage where feedback is unreliable

- clarifying acceptance criteria or Definitions of Done

- adjusting responsibility boundaries or feedback loops between stages

The objective is not more testing, but placing the most suitable tests at the stage where they deliver the highest economic value.

3) Earlier detection creates a reinforcing system effect:

- Shorter resolution times, because investigation and coordination are minimal

- Faster assignment and analysis, since context is still fresh

- Lower cognitive load, with fewer hand-offs and less re-learning

- Reduced defect management overhead, including less triage and backlog growth

As a result, teams spend less time working around existing defects and more time addressing the next set of meaningful problems — including those that only become visible once earlier issues are removed.

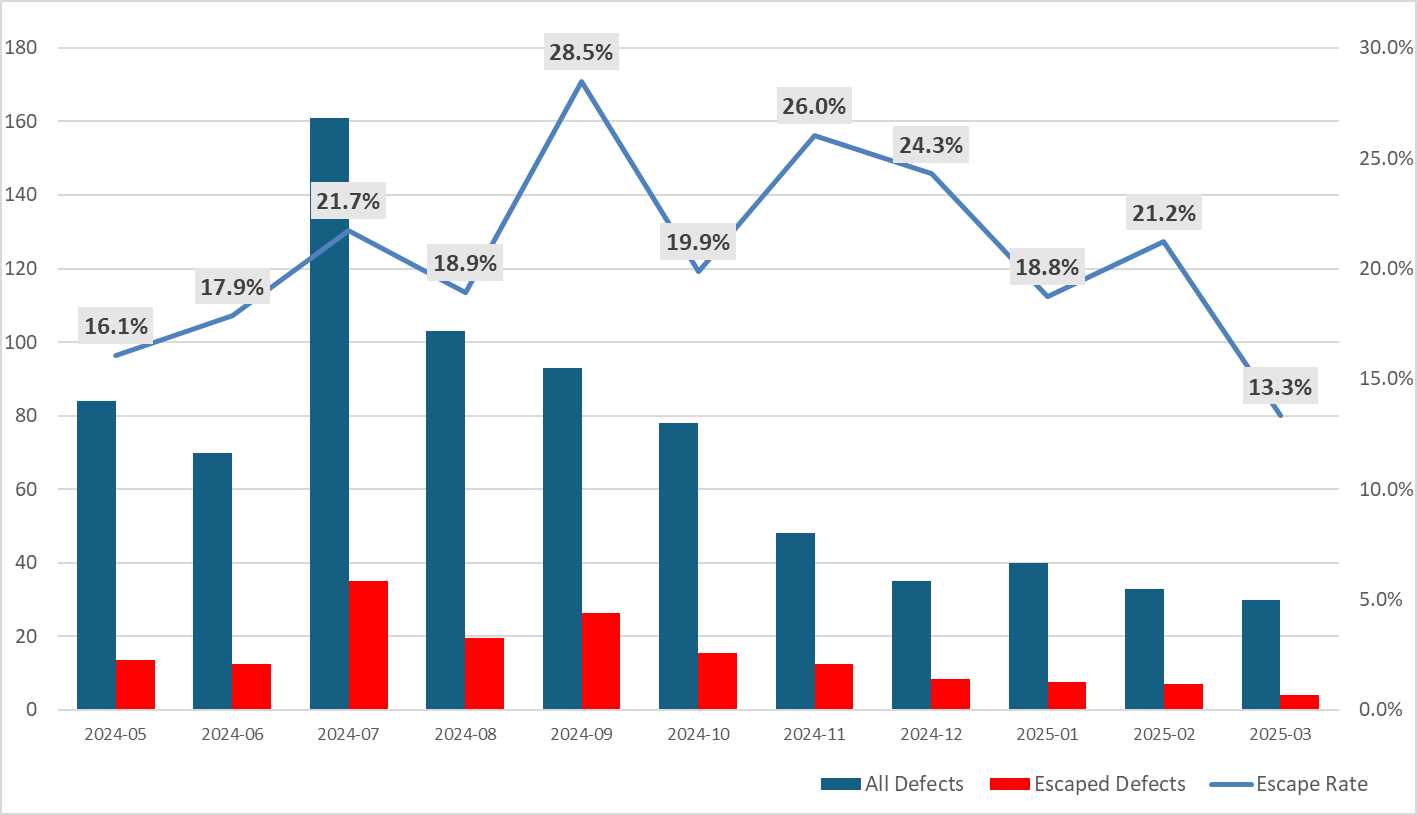

Measurement Views and Interpretation

A stage-specific DER view shows how many defects escape from one stage into the next. This makes it suitable for focused, local improvement – while keeping its scope intentionally narrow.

A system-wide DER view aggregates escaped defects across all stages. This reveals how detection gradually shifts upstream over time – and whether the total defect volume is decreasing, not just moving between stages.

Effective improvement is visible when:

- detection moves earlier

- feedback cycles shorten

- downstream rework decreases

- and overall defect counts decline

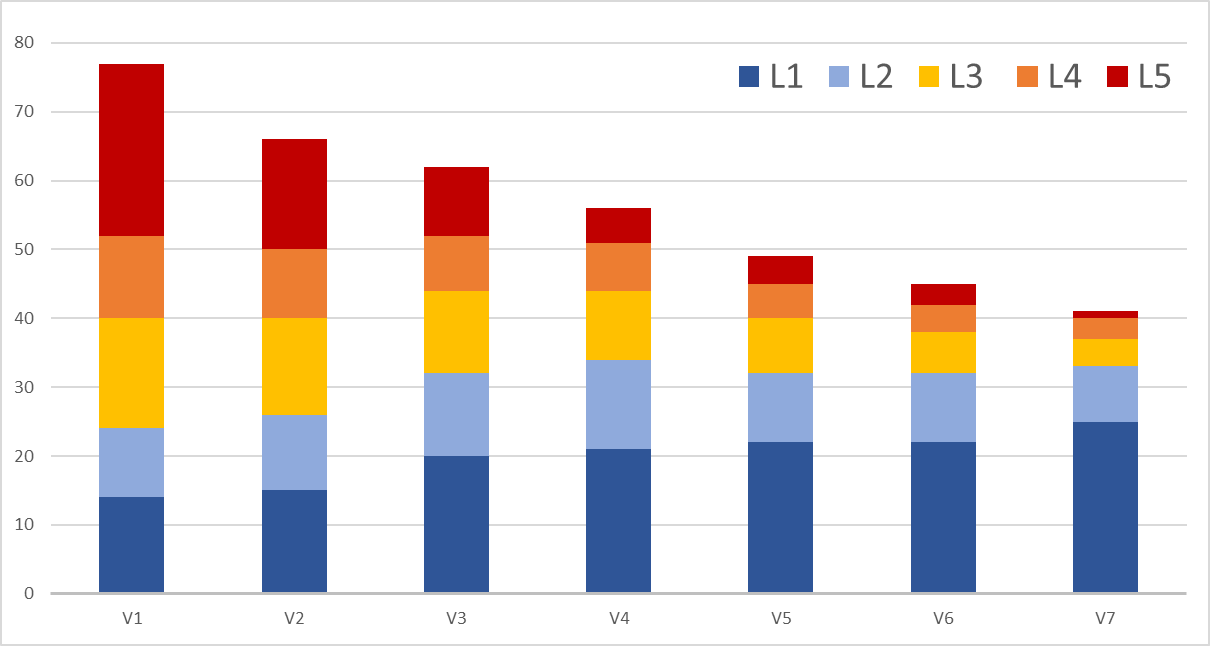

Defect Escape Rate can be measured by version1 rather than by time to avoid delayed and diffused feedback.2 Escaped defects are confirmed only when they are fixed or closed, which spreads defect data over weeks or months when viewed by calendar time. In addition, the same version reaches different test stages at different points in time. Time-based aggregation therefore mixes multiple versions and stages, obscuring improvement effects. Measuring by version keeps feedback coherent and makes iteration-to-iteration improvement clearly visible.

Why Shift-Left Does Not Happen Automatically

Despite its clear benefits, shifting defect detection earlier in the value stream does not happen naturally. It often conflicts with deeply rooted cognitive biases and organizational reward mechanisms.

From a human perspective, shift-left demands deliberate analysis and prevention – activities that require sustained focus and disciplined thinking. As described by Daniel Kahneman3, people naturally favor fast, intuitive decision-making over cognitively demanding analysis. This bias systematically favors reactive defect fixing over proactive defect prevention.

Organizational incentives frequently reinforce this tendency. Progress on functionality is visible and easy to reward, while early quality work remains largely invisible. In many organizations, late fixes, crisis response, and sustained overtime are treated as heroic achievements. Individuals and teams who “save the release” under pressure receive recognition, attention, and sometimes explicit rewards. This creates a structural anti-pattern: the system celebrates firefighting while unintentionally discouraging prevention.4

The delayed and indirect payoff of early quality work further weakens belief in shift-left practices. Analysis and prevention require upfront investment, while their benefits appear later as non-events – defects that never happen, incidents that never occur. Without system-level transparency, these avoided costs remain abstract and undervalued.

This is why Defect Escape Rate is essential. By making escaped defects visible per stage and over time, DER exposes the true cost of late detection and the tangible benefits of early prevention. It shifts the narrative from heroic recovery to systemic improvement and provides leaders with the evidence needed to realign incentives toward building quality into the system

The Tension Between Fast Feedback and Shift-Left

Fast feedback and shift-left are not opposites, but exist in a productive tension that must be resolved deliberately in the given context. Fast feedback emphasizes rapid learning, while shift-left turns recurring learning into prevention and automation. There is no universally “right” balance: different products, technologies, risks, and maturity levels require different choices. Practices such as test-first development, high test automation, and AI-supported development and testing can dramatically reduce the delay and cognitive cost of shift-left activities—and should be the default response whenever early quality work is perceived as “too slow” or “too expensive.” Defect Escape Rate supports this contextual decision-making by revealing whether fast feedback is compensating for missing prevention or whether early quality work is sustainably reducing downstream effort. In this way, shift-left becomes a conscious system design decision rather than a generic best practice.

Conclusion

Defect Escape Rate makes visible where a value stream fails to learn early enough. It connects quality, flow, and economics into a single, actionable signal.

Used well, DER shifts organizations from downstream firefighting to upstream system design. It enables teams to improve locally while optimizing globally – and helps leadership distinguish real progress from the mere relocation of problems.

In this sense, DER is not just a quality metric. It is a navigation instrument for building quality into the system.

References

- In this context, a version refers to an internal integration increment that is handed over to the next stage of the Assembly Line. It is not an end-user release. Versions are typically produced on a regular cadence (for example every one or two weeks) and represent the state of the system as it enters the next integration or test stage. Measuring escape rates by version preserves coherent feedback by linking defects to the specific increment in which they were introduced and detected. ↩︎

- This is especially valuable in value streams with long feedback cycles and multiple integration stages, where several product versions coexist at the same time. In large systems, it can take weeks for a change introduced at an early stage to reach later stages. As a result, while development at Stage 1 may already be working on version 10, Stage 5 or Stage 6 may still be validating version 6. Without making this lag explicit, feedback and resolution signals are easily misinterpreted. ↩︎

- Kahneman, D. (2011). Thinking, Fast and Slow. Farrar, Straus and Giroux. ↩︎

- From a system perspective, recurring heroics are not a sign of commitment or excellence – they are evidence that the value stream is compensating for missing prevention and insufficient early feedback. ↩︎

Author: Peter Vollmer – Last Updated on Januar 13, 2026 by Peter Vollmer