Organizing Around Value

Introduction

Value Stream Thinking makes the end-to-end flow of value visible. But visibility alone does not improve performance.

The Value Stream Lifecycle distinguishes three phases: identifying value streams, organizing around them, and systematically optimizing their performance. This article focuses on the second phase.

Once value streams are identified, a structural question emerges: Are our organizational boundaries aligned with how value actually flows?

Organizing around value is the structural response to that question. It is not a framework choice or a transformation slogan, but a design principle: if performance depends on flow, then structure must support that flow.

To understand why this matters, we begin with the structural problems that arise when value creation and organizational boundaries are misaligned.

The Problem to Solve

Visible Activity – Limited Flow

Many organizations experience a persistent gap between effort and outcome. Teams work at full capacity, initiatives are launched with urgency, and progress is continuously reported – yet delivery takes longer than expected. Integration issues surface late. Quality problems reappear. Dependencies dominate planning discussions. Meetings multiply, but clarity does not.

Despite visible activity and high utilization, the system does not flow smoothly.

Fragmented Responsibility and the Shifting Bottleneck

Certain functions may temporarily become “hotspots” and attract blame. They are escalated, pressured, and pushed to improve. Yet even when these teams work harder – and often they already are – the overall system does not stabilize. The bottleneck shifts. The pressure moves. The pattern remains.

In conversations about end-to-end performance, certain sentences appear with surprising regularity:

- “We delivered on time – the delay happened elsewhere.”

- “This dependency or issue is not our responsibility.”

- “It’s not us. The problem is upstream or downstream.”

These statements are rarely malicious. They are structural.

When responsibility is fragmented across functions, no one truly owns the end-to-end outcome. Each unit optimizes locally. The overall system suffers globally.

The symptoms are familiar:

- Projects that seem on track locally but stall at integration

- Priorities that shift because upstream or downstream work is delayed

- Rework caused by unclear ownership

- Increasing coordination overhead as systems grow more complex

In isolation, each issue appears manageable. Together, they reveal a deeper pattern: the organization works hard, but the system does not flow smoothly.

The Utilization Trap

A second reinforcing dynamic makes the situation worse: the pursuit of full capacity utilization.1

In many environments, high utilization is equated with efficiency. Every team should be fully loaded. Every specialist should operate at maximum throughput. All calendars are full with meetings. Idle capacity is seen as waste.

At the same time, organizations rarely run a single initiative. Multiple projects compete for the same limited resources. Each project has its own timeline, milestones, and sponsors. Each demands priority.

Under these conditions, project management often shifts from coordination to pressure amplification. Project managers act as watchdogs, accelerating escalation, requesting frequent status updates, negotiating resource allocations, and defending their project’s priority over others.

A growing portion of organizational energy is no longer spent on value creation, but on:

- Negotiating resource access

- Justifying progress

- Protecting timelines

- Managing cross-project conflicts

- Producing status transparency

This behavior is understandable. In a resource-constrained, multi-project environment, pressure seems rational.

But structurally, it reinforces the very dynamics that slow the system. Teams are split across initiatives. Work-in-progress increases. Context switching multiplies. Dependencies expand. And queues grow.

In complex systems with inherent variability, high utilization does not increase speed – it increases waiting time. As utilization approaches full capacity, even small fluctuations create waiting lines. Waiting time extends lead time. Extended lead times introduce further variability: priorities shift, integration contexts change, assumptions expire.

A reinforcing loop emerges: High utilization → queues → longer lead times → more variability → larger queues.

The Structural Paradox

The result is a paradox:

The more pressure is applied to accelerate delivery, the more organizational capacity is consumed by coordination rather than creation. The more projects are launched to increase output, the less effective capacity remains to complete any of them quickly.

What appears as acceleration becomes congestion. What appears as efficiency becomes delay. What appears as a performance problem is, in reality, a structural flow problem.

The question is therefore not: How do we push harder?

It is:

How do we design the organization so that value can flow – without structural resistance, fragmented responsibility, and self-inflicted queue accumulation?

Only when this question is addressed does the system have a chance to flow smoothly.

The Insight from Value Stream Thinking

If the problem is structural, then isolated improvements will not resolve it. Local efficiency gains cannot compensate for systemic friction. More detailed planning cannot eliminate queueing dynamics. Stronger oversight cannot remove fragmented responsibility.

What is required is a different way of seeing the organization. Most management discussions focus on activities, roles, and reporting structures. But these are representations – not the system itself. They describe who does what, not how value actually moves.

Value Stream Thinking shifts attention from functions to flow.

Instead of asking:

- Which department owns this task?

- Which project is responsible for this milestone?

- Who is accountable for this deliverable?

It asks:

- How does value move from initial concept to customer outcome?

- Where does work wait?

- Where do handoffs accumulate?

- Where does responsibility dissolve?

- Where do queues form?

This shift changes the level of analysis. The organization is not reduced to a collection of departments. Functional structures remain necessary for governance, capability development, and stability. But value creation does not follow hierarchical reporting lines. It flows across them.

Value Stream Thinking therefore introduces a complementary perspective: alongside the formal hierarchy, the organization is viewed as a system of interconnected value streams – each representing an end-to-end flow that transforms intent into outcome.2

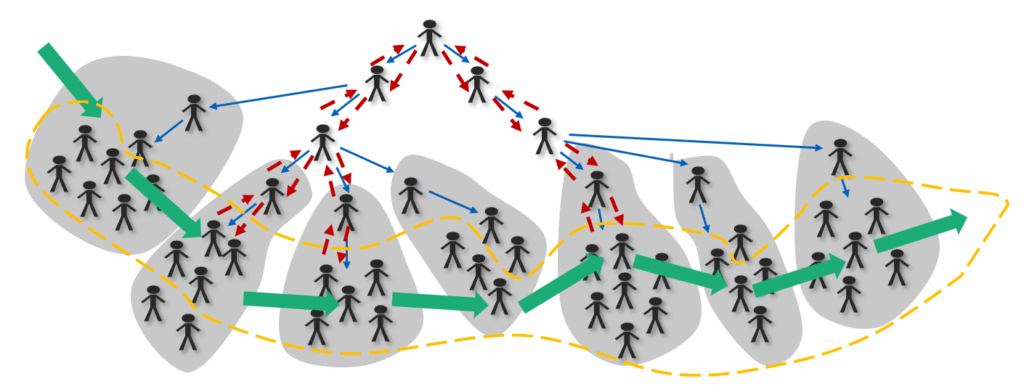

Red arrows represent formal hierarchical communication and governance structures.

The yellow boundary highlights the end-to-end value stream – cutting across departments while coexisting with the hierarchy.

Hierarchy organizes authority. Value streams organize value creation. Sustainable performance requires both – but aligned.

When the end-to-end flow becomes visible, structural misalignment becomes visible as well. Bottlenecks are no longer attributed to individuals, functions or departments alone. They are understood as consequences of boundary design, dependency structure, and capacity allocation.

Value Stream Thinking does not begin with reorganization. It begins with visibility. Only when value flow is understood can structural redesign become deliberate rather than reactive.

From Seeing Flow to Organizing Around Value

Once value flow is made visible, the structural implications become difficult to ignore. If performance depends on how smoothly value moves across boundaries, then the design of those boundaries matters. Organizational structures, team responsibilities, funding models, and governance mechanisms either support the flow of value – or obstruct it.

This does not imply that hierarchy must disappear. Functional expertise, compliance responsibilities, and capability development require stable structures. But when these structures are designed without regard to end-to-end flow, coordination overhead increases and queue accumulation becomes inevitable.

Organizing around value means deliberately shaping structures so that value streams can operate effectively. Instead of structuring work primarily around functions or temporary projects, organizations align long-lived teams and coordination mechanisms to the flow of customer value. Responsibility follows the stream. Accountability extends from initial intent to delivered outcome.

This shift does not eliminate hierarchy. It aligns hierarchy with flow. The question is no longer whether departments exist. It is whether value streams can move through them without friction.

Structural Consequence: From Visibility to Lifecycle

Once value streams are made visible, improvement cannot start with optimization alone. The Value Stream Lifecycle clarifies why. It distinguishes three fundamentally different phases:

- Identification – understanding and modeling the current flow

- Organizing Around Value – structurally aligning teams and responsibilities to that flow

- Systematic Optimization – continuously improving performance within the aligned structure

This sequence matters. If optimization begins while the underlying structure still fragments responsibility, improvement efforts are constrained by the existing design. Teams may achieve local maxima – but the system remains suboptimal.

This is the difference between local and global optimization.

Continuous improvement within the current structure moves the system toward a local maximum – better performance, but bounded by structural constraints. Organizing around value shifts the starting point itself. It changes the structural conditions under which optimization occurs. From there, continuous improvement can move the system toward a fundamentally higher global maximum. In lifecycle terms:

- Stage 1 makes the system visible.

- Stage 2 reshapes the system.

- Stage 3 improves the reshaped system.

Skipping Stage 2 means optimizing within inherited constraints. This is why organizing around value is not a transformation slogan. It is a structural prerequisite for global optimization.

Structural Alignment as a Design Discipline

Organizing around value is not a one-time transformation step. It is an ongoing design discipline.

Every organizational design embeds assumptions about:

- Where decisions are made

- How work is coordinated

- How cognitive load is distributed

- How accountability is defined

- How trade-offs are resolved

Structures shape behavior → Boundaries shape decisions → Decision rights shape flow.

Value Stream Thinking does not prescribe a fixed structure. It provides a lens for evaluating whether the current structure supports or constrains end-to-end value flow.

The ultimate test of structural alignment is performance – as reflected in the Value Stream Performance Parameters.

When structures enable decentralized decisions within clearly defined boundaries, deliberately manage cognitive load, and align accountability with value creation, continuous improvement can operate at a fundamentally higher level.

Organizing around value is therefore not an ideology. It is a structural precondition for global optimization.

Conclusion: Designing for Flow

Organizing around value is the structural expression of Value Stream Thinking. Once value streams are made visible, structural alignment becomes a design question. Boundaries must support flow. Decision rights must match accountability. Cognitive load must be managed deliberately. Governance must enable – not obstruct – end-to-end responsibility.

This is not a one-time transformation initiative. It is an ongoing design discipline. The purpose is not structural elegance.

The purpose is performance. When value creation is aligned with responsibility, when decentralized decisions operate within clearly defined boundaries, and when structures reflect the realities of flow rather than historical reporting lines, global optimization becomes possible.

The next question then naturally arises:

How should teams be designed so that stream alignment does not create cognitive overload?

How should interaction patterns between teams be structured to balance autonomy and coherence?

These questions move from structural alignment at the organizational level to structural design at the team level – a topic explored in the next article.

Notes & References

- The relationship between utilization, variability, and lead time is well established in queueing theory and product development economics. Don Reinertsen explains how cycle time increases non-linearly as utilization approaches 100% in The Principles of Product Development Flow (Reinertsen, 2009). Mary and Tom Poppendieck describe similar dynamics in lean product development contexts, showing how high work-in-progress and full utilization degrade flow and predictability in Lean Software Development (Poppendieck & Poppendieck, 2003).

Reinertsen, D. G. (2009). The Principles of Product Development Flow: Second Generation Lean Product Development. Celeritas Publishing.

Poppendieck, M., & Poppendieck, T. (2003). Lean Software Development: An Agile Toolkit. Addison-Wesley. ↩︎ - The idea of combining hierarchy and networked value creation is not new. Related thinking appears in John Kotter’s “dual operating system” (XLR8, 2014) and in frameworks such as SAFe. Value Stream Thinking sharpens this perspective by focusing explicitly on value streams and end-to-end flow.

Kotter, J. P. (2014). XLR8: Accelerate – Building Strategic Agility for a Faster-Moving World. Harvard Business Review Press. ↩︎

Author: Peter Vollmer – Last Updated on Februar 20, 2026 by Peter Vollmer